Guidelines for IoT security from the UK Government

On the heels of major security breaches related to the Internet of Things (IoT Devices) in recent years, the UK government released a new report this week outlining 13 guidelines it hopes to see become the standard for devices sold to consumers in the United Kingdom.

At the top of the list? No default passwords.

The average home in the UK has 10 smart devices and, as we wrote on our blog last week, the rapidly expanding surface area of the IoT means that potential attackers have a lot of potential entry points to gain access to a network. From unsecured light bulbs to a flaw that allowed hackers to use Apple HomeKit to unlock a user’s smart door, the press has been riddled with cautionary tales of seemingly innocuous ‘smart’ devices being the access point to millions of connected devices. Still, most cyber attacks that use IoT devices as a penetration point to a network tend to exploit one of several easy-to-address gaps in device security; for lack of a better term, most of these attacks occur because manufacturers fail to follow even basic device security protocols

The UK's Department for Culture, Media and Sport released "Secure by Design," a set of guidelines for IoT device security.

After last year’s Mirai botnet attack took down some of the world’s most popular websites by initially infecting a host of unsecured devices, governments began to ramp up their research efforts on IoT security. The first major report to come out of these efforts is Secure By Design from the UK Department for Culture Media and Sport, written in conjunction with the National Cyber Security Centre. The paper cites two overarching concerns regarding the future of IoT:

- Consumer security, privacy, and safety are being undermined by the vulnerability of individual devices.

- The wider economy faces an increasing threat of large-scale cyber attacks launched from large volumes of insecure IoT devices.

The authors also outline thirteen key recommendations for any and all new IoT devices being marketed and sold in the UK and said that the report, “advocates a fundamental shift in approach: moving the burden away from consumers having to secure their devices and instead ensuring strong security is built into consumer “Internet of Things” (IoT) products by design. “

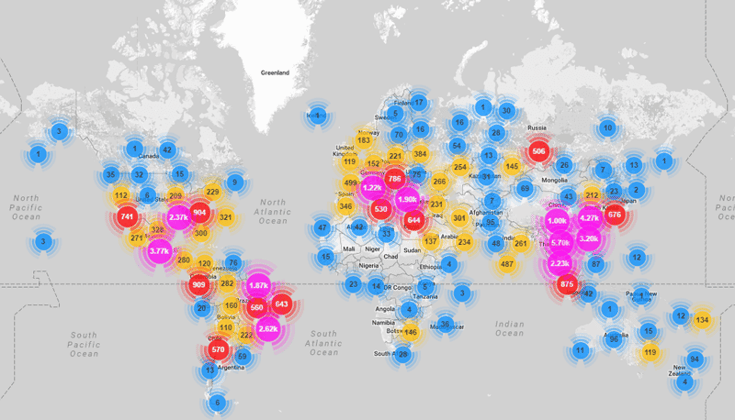

A heatmap showing the scope and scale of the Mirai Botnet attack, which was launched via unsecured IoT devices

At the core of the report is a Code of Practice, ”aimed primarily at manufacturers of consumer Internet of

Things products and associated services, [and] that is the product of years of internal research by the UK Government.” The Code of Practice can be a bit surprising - It mostly seems to cover having a basic security development lifecycle - but the promise of quick profits for the latest smart gadgets often mean security is overlooked in the rush to get a product to market. "If we've learned anything from countless attacks on smart devices in recent years, it's that manufacturers have been rushing to get the latest devices to market without properly considering the security implications," said Richard Parris, CEO of security firm Intercede

The thirteen recommendations, in order of priority as defined by the UK, are

1) No default passwords

- All IoT device passwords must be unique and not resettable to any universal factory default value.

2) Implement a vulnerability disclosure policy

- All companies that provide internet-connected devices and services must provide a public point of contact as part of a vulnerability disclosure policy in order that security researchers and others be able to report issues.

3) Keep software updated

- All software components in internet-connected devices should be securely updateable. Updates must be timely and not impact the functioning of the device.

4) Securely store credentials and security-sensitive data

- Any credentials must be stored securely within services and on devices. Hardcoded credentials in device software are not acceptable.

5) Communicate securely

- Security-sensitive data, including any remote management and control, should be encrypted when transiting the internet, appropriate to the properties of the technology and usage.

6) Minimise exposed attack surfaces

- All devices and services should operate on the “principle of least privilege”; unused ports must be closed, hardware should not unnecessarily expose access, services should not be available if they are not used and code should be minimized to the functionality necessary for the service to operate.

7) Ensure software integrity

- Software on IoT devices must be verified using secure boot mechanisms.

8) Ensure that personal data is protected

- Where devices and/or services process personal data, they should do so in accordance with [existing] data protection law.

9) Make systems resilient to outages

- Resilience must be built into IoT services where required by the usage or other relying systems, such that the IoT services remain operating and functional.

10) Monitor system telemetry data

- If collected, all telemetry such as usage and measurement data from IoT devices and services should be monitored for security anomalies within it.

11) Make it easy for consumers to delete personal data

- Devices and services should be configured such that personal data can easily be removed when there is a transfer of ownership when the consumer wishes to delete it and/or when the consumer wishes to dispose of the device. Consumers should be given clear instructions on how to delete their personal data.

12) Make installation and maintenance of devices easy

- Installation and maintenance of IoT devices should employ minimal steps and should follow security best practices on usability.

13) Validate input data

- Data input via user interfaces and transferred via application programming interfaces (APIs) or between networks in services and devices must be validated

"We want everyone to benefit from the huge potential of internet-connected devices, and it is important they are safe and have a positive impact on people's lives,” said Minister for Digital and the Creative Industries Margot James. "We have worked alongside industry to develop a tough new set of rules so strong security measures are built into everyday technology from the moment it is developed."

Still, the Code of Practice is merely a set of guidelines. It is not, in any way, binding and that has many experts worried:

What is not so clear is whether this new voluntary code of practice will make any difference. The key word is voluntary. The kind of manufacturers who will sign up to a code are probably pretty responsible already but there are plenty of others whose only aim is to pile their insecure products high and sell them cheap. The new policy will work only if online retailers refuse to stock products that do not comply with the code.

- Rory Cellan-Jones, technology correspondent for the BBC

The UK government itself seems to recognize this and sees the recommendations as more of a first step in the right direction. Minister James said of the recommendations, “This will help ensure that we have the right rules and frameworks in place to protect individuals and that the UK continues to be a world-leading, innovation-friendly digital economy.”

Whether these recommendations eventually become UK common law remains to be seen, but they would certainly appear to be an important step forward toward the adoption of more global industry standards for security practices with devices connecting to (and potentially compromising) the Internet of Things.

Read more: